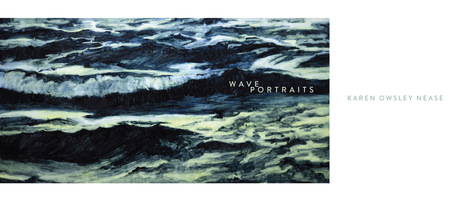

Book cover

The following essays are from a book about my artwork. To view the book, just click on the little Adobe Acrobat icon to the right. It is a beautiful little book showing the paintings from my solo exhibition at the Kruk Gallery, University of Wisconsin - Superior. The book was designed by graphic artist Stacie Renne.

Karen Owsley Nease and the sentient landscape.

Karen Owsley Nease’s Wave series draws from the traditions of Western landscape painting, and subverts those traditions as firmly as it refers to them. By doing so she invites us to change the way we view the non-human world which surrounds and forms us.

Her dark color palette and muscular mark making are beautiful, but not inviting in the manner of traditional Western landscapes. Over the centuries the genre has tended to emphasize human ownership or control of the land, or rendered scenes for the aesthetic enjoyment and emotional gratification of the viewer. Some works—especially seascapes-- have depicted turbulent and menacing scenes, but these have often been backdrops for human dramas, such as shipwrecks, classical myths, or biblical stories.

Nease’s work lacks any narrative matter, but instead presents us with the elemental, merciless, and completely indomitable force of water, the only actor in her visual space. One finds no reference to anything human when viewing them, except for our own reaction of smallness, powerlessness and awe. The paintings confront us like a wall of water surging toward us.

The painting further bypasses traditional landscape work in that any attempt we make to distinguish foreground from background, or to find a solid object to act as a hook for our attention, fails. Instead, the paintings invite us into a way of seeing that diverges from the dominant mode we learn as school children in the industrialized West.

Instead of offering us discrete objects set against a background, Nease interweaves multiple points of focus into one animate Whole. And in the paintings that do exhibit a strong focal point (see l’Origine du monde, and The Oxbow), we are not looking at any object so much as we are viewing an absence, or a doorway into deep space.

One might be tempted to view Nease’s Wave series and assume she’s inspired by the Romantic tradition, but that assumption would be wrong. Nease does not fuel her creative process with her emotional responses. Her working method is patient and precise. Starting with her own gridded photographs, she brings the machine-made images to life slowly and deliberately. And although her images arise partly from machine and grid, they come to life through her remembered somatic responses to the felt presence of those waters.

Unlike many artists, she has a background in architecture and the sciences. She understands the scientific method and the discipline of rational inquiry, but uses them to express the voice of the more-than-human world around us. Her interest in this world extends to all life forms, whose interbeing forms the living cloth that blankets our planet. She has studied plant, animal (both vertebrate and invertebrate) and soil interactions, and has used that knowledge to restore native wildlife habitats. Her experiences of working with living systems has honed an artistic vision which straddles the conceptual categories of animal, vegetable, and mineral: like the currents and eddies of her painted seascapes, Earth’s DNA-based life and the periodic elements interact in a constantly shifting and intelligent exchange, creating a fluid moving structure, like “a maze whose walls rearrange themselves with each step you take.” (1)

Nease’s work has sprung out of a growing movement in the arts and sciences which invites us into a liminal space on the verge between the human and transhuman realms. Within this marginal dimension the world abides as a subject rather than a collection of objects. Those who venture into this borderland will discover a paradox: removing ourselves from the center of the picture does not diminish us, but rather expands the depth and breadth of what we may see and become.

Ruth Henriquez Lyon

Writer, artist, and wildlife gardener

(1) Gleick, James. Chaos: Making a New Science, 1987, 24.

The “Wave” Series of Karen Owsley Nease

When she first visited Duluth, MN, in the mid-1990s, Karen Owsley Nease knew that she had stumbled upon subject matter that could possibly last her a lifetime. The ever-changing light on Lake Superior, which borders a city that’s often called the San Francisco of the Midwest, was a huge source of fascination for the artist, who describes herself as a “child of flat horizons.” Since moving there a few years ago, she’s had ample opportunity to study the lake’s mutable surface in all kinds of weather.

Nease grew up in landlocked Kansas City, and studied both art and architecture, acquiring two degrees in the latter subject from the University of Kansas. Those two facets of her biography carry over in ways that may not be immediately evident to viewers. Of course, an artist growing up in the Midwest, on the edge of the Great Plains, is bound to be fascinated with the rhythms and waves of a mighty body of water, but Nease, because of her geographical heritage and newly adopted home, is also captivated by horizons in general, and these became the subject of an earlier series by the artist.

The architectural component of her training enters into her process, again in ways that are not superficially evident. As with designing a building, from blueprint to final structure, Nease thinks through her “Wave” paintings beforehand. “I know what the paint will look like before I even apply it,” she says. Photography also helps her with source material: She can take pictures on a cellphone, load them into Photoshop, use a crop tool to find her image, and blow up details to study the myriad textures of water. And water does have texture, as Nease conveys again and again in the series—from the mysterious inky depths of waves to relatively calm patches to foamy crests. But where another painter might depend on varying thicknesses of pigment to convey those qualities, this artist builds up her pictures in glazes until the surface reaches a seductive luminosity.

The paintings may take her from a couple of weeks for a medium-sized work to a few months for one of the larger pieces, which can reach ten feet in length. Maybe the most spontaneous part of her process is in finding the titles: While researching the works and realizing them on wood panels, a detail might surface that suggests a movie, a work of art, a piece of music, or even a wildflower. So The Oxbow brought to mind Thomas Cole’s famous painting from 1835 of the that loop in the Hudson River. Charge of the Light Brigade, though relatively small, summoned for the artist the thundering force of the poem and movie of the same name (or possibly the profusion of foamy crests provoked a play on words.) When she was painting Corleone, Nease says, she kept thinking of old stone walls in Sicily, where Michael Corleone of the “Godfather” movies went to hide out after the Mafia bloodbath in New York.

Lakes, oceans, rivers, and other bodies of water have proved of enduring fascination to artists. And it’s not hard to understand why: Water offers perhaps as much—or even more—mystery, intricacy, and variety than the human body. Leonardo repeatedly strove in his sketchbook to understand the mechanics of waves and eddies. Turner was drawn to the elemental forces of storms at sea. Homer loved the glassy stillness of the Caribbean as much as the tempestuous squalls around Prouts Neck in Maine. In her meticulous drawings, Nease’s older contemporary Vija Celmins brings to the surface of water a profoundly meditative impulse. And what Nease herself offers us is a painterly appreciation of the slippery complexity of Lake Superior. The “Wave” series also keeps viewers pleasurably off balance, flirting with abstraction even as the particulars of water—the knifelike edge of surf, the dark recesses inside a breaker, or the translucency of the shallows—bring us back to the reality of the mysterious substance that covers almost three-quarters of the planet.

Ann Landi

Contributing editor, ARTnews; founding editor, Vasari21.com